Financial statement analysis Analytical tools are used to general-purpose financial accounts and related data in order to make business choices. Accounting data must be transformed into more relevant information. Our dependence on hunches is reduced through financial statement analysis. guesses and instincts, as well as our decision-making uncertainties It has no effect on the It eliminates the need for expert opinion by providing us with an effective and methodical foundation for decision-making. commercial decisions This section defines the objective of financial statement analysis and the data it contains. sources, the use of comparisons, and various computation difficulties .

Purpose of Analysis

Internal accounting information consumers are those involved in the company's strategic management and operations. Managers, officials, internal auditors, consultants, budget directors, and market researchers are among them. For these customers, the goal of financial statement analysis is to give strategic information to increase firm efficiency and effectiveness in supplying products and services.

External consumers of accounting information are not directly involved in the operation of the business. Shareholders, lenders, directors, customers, suppliers, regulators, attorneys, brokers, and the press are among them. External users rely on financial statement analysis to make more informed judgments in pursuit of their own objectives.

Other applications of financial statement analysis can be identified. Shareholders and creditors evaluate a company's prospects before investing or financing. A board of directors examines financial accounts in order to keep track of management's choices. Financial statements are used in labor discussions by employees and unions. Financial statement information is used by suppliers to create credit conditions. Customers examine financial accounts while selecting whether or not to form supplier connections.

Customer tariffs are decided by public utilities by examining financial statements. Financial statements are used by auditors to examine the "fair portrayal" of their customers' financial results. Financial statements are used by analyst services such as Dun & Bradstreet, Moody's, and Standard & Poor's to make buy sell recommendations and determine credit ratings. These consumers all have the same purpose in mind: to analyses the performance and financial status of the organization. This involves assessing (1) past and current performance, (2) current financial position, and (3) future performance and riskBuilding Blocks of Analysis

The analysis of financial statements focuses on one or more aspects of a company's financial situation or performance. Our approach prioritizes four areas of investigation in various degrees of relevance. This chapter describes and illustrates four topics that are considered the foundations of financial statement analysis:

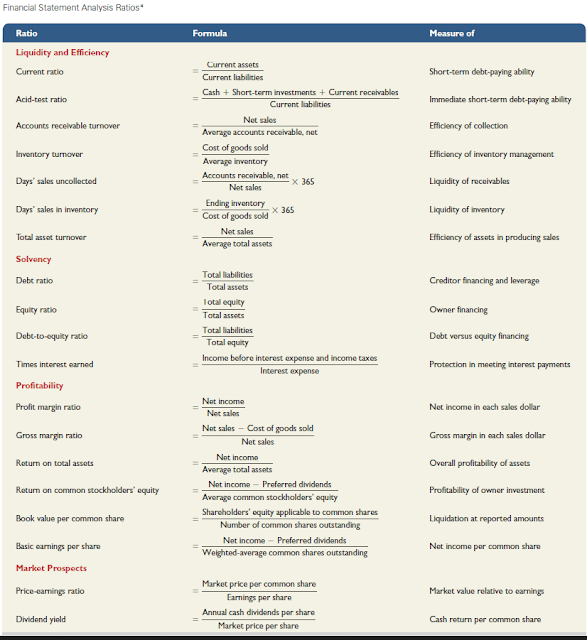

● Liquidity and efficiency—ability to meet short-term obligations and to efficiently generate revenues.● Solvency—ability to generate future revenues and meet long-term obligations.

● Profitability—ability to provide financial rewards sufficient to attract and retain financing.

● Market prospects—ability to generate positive market expectations.

Applying the financial statement analysis building blocks entails defining (1) the objectives of analysis and (2) the relative importance of the building elements. We differentiate between these four building blocks to highlight distinct elements of a company's financial state or performance, but we must keep in mind that these areas of study are interconnected. For example, the availability of finance and short-term liquidity circumstances impact a company's operating performance. Similarly, a company's credit status is determined not just by its capacity to meet short-term liquidity needs, but also by its profitability and asset utilization efficiency. We must identify the relative importance of each construction piece early in our investigation. As a result of the evidence gathered, emphasis and analysis may shift.

Information for Analysis

Some users, such as managers and regulatory bodies, can request unique financial reports tailored to their specific analytical requirements. However, the majority of users must rely on general purpose financial statements consisting of (1) an income statement, (2) a balance sheet, and (3) a statement of stockholders' equity (or statement of retained earnings), (4) cash flow statement, and There are five (5) notes to these assertions.Financial reporting is the sharing of financial information that is relevant for making decisions. Investment, credit, and other commercial choices Not only does financial reporting contain general-purpose financial statements, as well as information from SEC 10-K and other filings Press announcements, shareholder meetings, predictions, management letters, auditors' reports, and other documents Webcasts.

One example of important information other than standard financial statements is Management's Discussion and Analysis (MD&A). For example, Research In Motion's MD&A (accessible at RIM.com) begins with an introduction, then moves on to essential accounting policies and restatements of past statements. It then goes into operating outcomes and financial position (liquidity, capital resources, and cash flows). The remaining sections go into legal proceedings, financial instrument market risk, disclosure controls, and internal controls. The MD&A is a great place to start when learning about a company's operations.

Standards for Comparisons

When interpreting financial statement analysis metrics, we must evaluate if the measurements imply excellent, terrible, or average performance. To make such decisions, we require comparison criteria (benchmarks) that comprise the following:● Intracompany—The company under analysis can provide standards for comparisons based on its own prior performance and relations between its financial items. Research In Motion’s current net income, for instance, can be compared with its prior years’ net income and in relation to its revenues or total assets.

● Competitor—One or more direct competitors of the company being analyzed can provide standards for comparisons. Coca-Cola’s profit margin, for instance, can be compared with PepsiCo’s profit margin.

● Industry—Industry statistics can provide standards of comparisons. Such statistics are available from services such as Dun & Bradstreet, Standard & Poor’s, and Moody’s.

● Guidelines (rules of thumb)—General standards of comparisons can develop from experience. Examples are the 2:1 level for the current ratio or 1:1 level for the acid-test ratio. Guidelines, or rules of thumb, must be carefully applied because context is crucial.

All of these comparison criteria are beneficial when used correctly, but measures collected from a specific rival or set of competitors are frequently the best. Intracompany and industry measurements are also critical. Guidelines or rules of thumb should be used with caution, and only if they appear acceptable based on previous experience and industry standards.

Tools of Analysis

Three of the most common tools of financial statement analysis are1. Horizontal analysis—Comparison of a com Pany’s financial condition and performance

across time.

2. Vertical analysis—Comparison of a company’s financial condition and performance to a

base amount.

3. Ratio analysis—Measurement of key relations between financial statement items.

Resources : fundamental accounting principles 20th edition (pdf) John J. Wild , Ken W. Shaw Barbara Chiappetta